- Home

- David McCullagh

The Reluctant Taoiseach Page 3

The Reluctant Taoiseach Read online

Page 3

Among the lecturers Costello got to know were James Murnaghan, later a judge of the Supreme Court, Swift MacNeill, then an Irish Party MP, and Arthur Clery, whose favourite pupil he was.63 George O’Brien described the latter lecturer: “Clery was a bachelor who liked the society of young men. He used to invite us to very pleasant dinner parties where we met some of his own generation. He was kind to us and I appreciated his friendship at the time. I learned later that he was very bigoted against the British and against Protestants and a great extremist in politics, although he took no active part in revolutionary movements. I am afraid he influenced some young men in the direction of his own views and that he sowed the seeds of a good deal of bitterness.”64 As O’Brien’s biographer makes clear, this somewhat jaundiced account may have been influenced by O’Brien’s dislike of John A. Costello.65

As a later interviewer put it, “in college his interests were intellectual rather than athletic”,66 but the young Costello did have some sporting interests—he was a member of a football club based at Goldsmith Street.67 However, he was to have a more enduring interest in golf. He joined a golf club in Finglas,68 a forerunner of his membership of clubs at Portmarnock, Milltown and Rossapenna, Co. Donegal. He also, at least occasionally, was prevailed upon to sing at musical evenings.69 According to his children Declan and Eavan, he spoke in later years about singing at parties as a young man, sometimes accompanied by his wife, Ida, on the piano.70 Costello also regaled his children with reminiscences of the 1907 Great Exhibition in Ballsbridge, with its giant water slide and a Zulu tent featuring “real live Africans”, obviously an exotic sight at the time.71

In July 1911, just turned 20, Costello wrote a lengthy and mildly amusing article for the National Student, the college magazine, contrasting the old Royal with the new National University, suggesting that he saw some improvement in the situation of students. He claimed that the Royal “was little better than a glorified Boarding and Day School … The residents … rose in the morning by rule, lived mechanically, and even voted in the Societies mechanically and as they were told. The outdoor students of the College came to lectures, met casually, chatted desultorily outside the lecture room, and dispersed.” The new structure had a higher purpose than the old, which had served merely as an exam factory. “The National has been created to send forth students better equipped mentally and bodily than heretofore; to produce students with broader views and wider knowledge … Its aim should be culture rather than erudition; learning rather than pedantry.” Exams, he suggested, were “a necessary evil, and must be tolerated … The importance attached to them should, however, be reduced to a minimum: the true end of a real University should be culture, not examination.”

Of his fellow students, he observed mordantly that “students always take themselves and their opinions seriously”, before going on to criticise certain “types” of student, which could be divided into sots and swots. Of the first, he wrote, “These gentlemen often accost some meek and unoffending student whom they wish to impress; buttonhole him and tell him of the number of times they were on the bend; how hard it is to study when in such a state; what head-aches they had after it; what daring tricks they had played on their professors; and what damage they had done to other people’s property. These gentlemen in their first year wish to make it believed that they are real wits and veritable roués!” (It is impossible to know who Costello had in mind when he was writing this, but it sounds rather like the “dissipated” student Kevin O’Higgins, as described by his biographer, a regular at Mooney’s pub in Harry Street.)72

Costello had this to say about the swots: “They walk rapidly, at the sound of the bell, from the Library to the lecture hall and install themselves in a place convenient to the professor and without losing an instant. They are fearful of being late. They are fearful of losing some of the words of wisdom which fall from the learned professor’s lips. They are fearful of incurring his ire. They take copious and meticulous notes and accept his opinions as final without demur. The lecture finished, they hasten back to their interrupted studies. No loitering, no conversation, no stories—all study concentrated and unlimited. No Society ever sees them. At social functions they are conspicuous by their absence—nor are they missed. Their one desire is success in examinations, and their one aim is to stuff their brains with a store of book learning, thereby taking the shortest path to pedantry.”

This leads him on to extol the virtues of the College societies, which are beneficial and, in fact, indispensable. “By means of books we may come under the influence of dead genius; by means of social intercourse we may be influenced by living talent. For the formation of student character there must be frequent conversation between the students, they must live and work together, and must get to know each other. What a blank student life would be if it merely consisted of daily attendance at lectures!”

Given his experience in the Literary and Historical Society (the L&H), his assessment of the quality of debate there is interesting: “The ideas of the members of these societies may not, and seldom are, either strikingly original or alarmingly learned, but at all events by speaking in public they are taught self-confidence and self-mastery, and even from listening to commonplace and mediocre ideas there is something to be gained … The real raison d’être of College Societies is to be found in the fact they are conducive to culture and refinement, and that fluency of speech in public is as much an acquired talent as a natural gift.”73 He was an example of the truth of this observation—his future success in politics and the law was built on his ability as a public speaker, an ability honed in college debates.

It is possible that involvement in college societies conferred culture and refinement on students, but a more immediate reward was status—especially in the L&H, success in which “was firmly established as a significant benchmark against which any ambitious student’s career in university was measured”.74 As Costello later observed, the lack of resources under both the old Royal and the new National Universities denied students the university life known in older academic institutions, but “they made it for themselves by congregating around the steps of the National Library, and by their activities in the famous Literary and Historical Society”.75

The Library steps, according to George O’Brien, “were the scenes of much conversation. The conversations on the Library steps in Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist bring back vivid memories of the hours that we used to spend on the same spot …”76 The L&H, meanwhile, was the place where “many of the young men who helped to establish the new Irish State from 1922 onwards received their first lessons in politics and public speeches”.77 If UCD was where the future elite of the Irish Free State met, the L&H was where they cut their teeth, learned the arts of public speaking and of politics, and made friendships and enmities that were to last a lifetime. Those young men included John A. Costello. He later claimed that his first appearance in print was as a “Voice” during an address by Chief Secretary Augustine Birrell to the L&H in the Aula Maxima in 86 St Stephen’s Green. He “was at the back of the hall, a very young student in my first year, and very tentatively I am afraid shouted out ‘What about the new University?’”78

A contemporary, slightly tongue in cheek, description of the L&H sets the scene: “About a hundred and twenty people, some eighty men and forty women, sit from 8 p.m. till 11 p.m. in a room decorated with grisly pictures of skeletons [meetings were held in the same room as medical lectures], and in an atmosphere almost solid with tobacco-smoke. The first hour is occupied with a ‘discussion of rules’. The majority of the meeting have not the least idea what the rules are, but a handful of men spend an hour heckling the officers of the Society with regard to them … The debate begins … It was perfectly obvious to me after listening to a very few of the speeches that the real object of a speaker was not to say something new or weighty … but to talk good nonsense …”79

Chief among the hecklers was Costello’s brother, Tom, a flamboyant figure who had pre

ceded him to UCD in 1907 and was studying medicine.80 The elder Costello quickly made a name for himself as a tormentor of the Society’s officials: “There are some who expend, in inventing posers for the Record Secretary, a wealth of time and ability that, otherwise applied, would make them medallists of the society. But … [Mr] Costello … and others of that ilk prefer asking questions to making speeches. And the society would be much duller if they did not.”81 Arthur Cox, a friend and rival of Jack Costello’s, described Tom as “dominant in private business. Caring little for more formal debate, he seemed to be for ever in opposition, thundering from the topmost bench down on the committee at their table below, moving votes of censure and perpetually taking the officers to task for some breach of Palgrave’s Parliamentary Procedure which ruled all our proceedings. Had he remained in Ireland … he would have been a leader.”82 Another contemporary, Michael McGilligan, said, “Tom was at that time the more dynamic of the two. Tom laid about him in the Society … Jack … was not then the Costello of the Courts …”83

The younger Costello was very much overshadowed in his first few years in college by his brother, as is shown in the pages of the National Student, where Tom was frequently a target for good-natured banter. When Jack was mentioned, it was usually in relation to his more flamboyant brother.84 The younger Costello made his maiden speech to the L&H in November 1908, shortly after starting in UCD. The then auditor, Tom Bodkin, later a good friend, remembered the speech as being “on the trite subject: ‘That the pen is mightier than the sword’”,85 while Costello described it as “most undistinguished”.86 It appears he was right—his effort received the lowest score of any speaker that evening, at just 3.92 out of 10.

In February 1911, Tom Costello’s badgering of the committee finally produced results, and led to advancement for him and his brother. Tom’s motion of censure on the committee was passed by the necessary two-thirds majority.87 Elections were held for a new committee. Arthur Cox topped the poll, with 46 votes. Jack Costello was second, with 39, one more than Tom.88 As a speaker, Jack Costello had not yet hit his stride. The National Student observed, “One cannot get over the idea that he does not believe in what he is saying … that he makes no distinction between his strong and his weak points—that he is not impressive.”89 He was, for instance, ranked twentieth out of 23 speakers in the impromptu debate in May (which was won by Arthur Cox, with Patrick McGilligan second),90 despite a fairly easy topic—“That the worst of things must come to an end”. His brother, the National Student noted, “denied stoutly, for several reasons, mainly personal, ‘That a large mind is impossible in a small family’ …”91

Drama was provided by the 1911 auditorial election between Patrick McGilligan, the previous year’s runner-up, and John Ronayne. A contemporary account read, “Who that has been through it either as active partisan or harried voter will ever forget it? … It was the final incident in the fierce struggle that has been going on between the two parties in the Society … the parties may well ask themselves what they were fighting for, and what is their exact point of difference … we do wish to deprecate the excessive bitterness which marred, grievously marred, the late election …”92 Michael McGilligan described the campaign as having “bitterness of a kind and degree that I had not seen in any previous election. I do not remember why: I am not sure that I ever knew why …”93

Ronayne was declared the victor, by 83 votes to 80, but a petition was immediately lodged challenging the validity of a number of the votes. The row was so bitter that the President of UCD, Dr Denis Coffey, asked for legal advice from the Solicitor General, Ignatius O’Brien, himself a former auditor (and later Lord Chancellor). O’Brien ruled that a number of the votes for Ronayne were indeed invalid, and recommended a new election. Dr Coffey wisely decided to avoid a further divisive contest, and instead proposed a compromise, with Ronayne to continue as auditor until (perhaps appropriately) St Valentine’s Day, when McGilligan was to take over. This compromise was ratified by the Society on the proposal of Jack Costello,94 though Ronayne later attempted to repudiate it.

The split in the Society appears to have left the Costello brothers on different sides—when it came to the division of offices within the committee, Tom first proposed Alec Maguire, who declined the nomination, and then Arthur Cox as Correspondence Secretary, in opposition to Jack. The younger Costello, however, was elected to the post by five votes to three. Tom was Records Secretary and Michael J. Ryan was Treasurer. Cox had been nominated for all three posts, and lost all three.95 One of Jack’s more novel suggestions on the committee was for the society to hold a dance—a proposal later vetoed by Dr Coffey.96 This was perhaps an attempt to appeal to members in advance of the next auditorial election.

In debate, meanwhile, Jack Costello was now a very regular contributor, with improved though still not spectacular marks—although by now he was occasionally beating Arthur Cox in debate as well as in elections.97 As the National Student put it, “Mr Cox has, we think, the best style of speaking in the Society. While he is speaking he is very impressive, it is only when he has sat down that one is tempted sometimes to think that he has said nothing and said it very well. Mr Jack Costello is an example of the value of practice. He improves every meeting and is now really worth listening to …”98 In May, he read a paper on “Ireland’s Literary Position” to the Society, receiving the very high mark of 9.16 out of 10.99 According to the account in the National Student, he “enhanced his reputation by the excellence of his paper. It was so good … that his brother sat beaming with a look on his face which said quite plainly, ‘See what I could have done if I had only bothered’.”100

This paper was delivered in the midst of an auditorial election campaign, which pitted Costello against Arthur Cox. Cox, who was to become Ireland’s leading solicitor in mid-century, was a Belvedere boy from a well-off family—his father, Dr Michael Cox, was the closest friend of John Dillon, at this point deputy leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party.101 He and Costello were to be friendly rivals for many years, although at this time the rivalry rather than the friendship was dominant, certainly as far as Cox was concerned. In later years, Cox remembered the campaign as intense, because “electioneering tactics had been brought to a high perfection … no device was omitted by the supporters of either”.102 Costello’s recollection was probably more accurate: “I was the complete amateur. He knew every trick in the bag and always defeated me.”103 In February 1961, a half century after the contest, Costello presided over a meeting of the L&H “and spoke of how he had been deprived of that office … by the ruthless methods of that most respectable Dublin solicitor Mr Arthur Cox. It was clear that the result still rankled after all the years.”104

On nomination night, Cox was proposed by George O’Brien, who, in the lively account of the National Student, “gave us a list of Mr Cox’s successes from his earliest childhood up to the time he became a nut and went to dances. Nobody blames Mr Cox for winning a lot of medals—everyone must have his little hobby—but everyone blames Mr O’Brien for reminding us of them. Mr Davoren seconded, and in polished tones talked about the magnificent speeches which Mr Cox had made at every meeting of the society. As Mr Davoren had been present at not more than three meetings this year his opinion on the subject was of undoubted value. Mr C.A. Maguire proposed and Mr Dwyer seconded Mr J. Costello. They told us, of course, that Mr Costello had had ‘the interests of the Society at heart’, and had read a magnificent paper, and so on … All the voters on the authorised list—to the number of 200—listened breathlessly to the speeches … There were also many present whose subscriptions had been paid, but who did not know Mr Ryan, the treasurer, who were so unbiased that they did not know which was Mr Costello and which was Mr Cox, and who went out as they came in—with their minds made up for them. That insignificant minority, the lay, stay-a-thome members who had attended regularly during the year and had paid their own subscriptions, sat there unnoticed and unaddressed. What did their votes matter?”105

The final touch of brilliance on the part of the Cox campaign was to appeal to female members. Admission of women had been a controversial subject in the Society until 1909, when they had outmanoeuvred their opponents by the simple expedient of paying their subscriptions to the Treasurer. Auditor Michael Davitt then ruled that as paid up members they could themselves vote on whether or not they should be admitted.106 Both Costello and Cox had spoken against the admission of women, but the latter appears to have been more committed to the anti-suffragette cause, even telling a debate at the King’s Inns that women cause wars, as was proved by Helen of Troy.107 But an election is an election. A number of female members informed Cox that they would not vote for him unless they were invited to the traditional auditor’s victory tea in the Café Cairo, which, equally traditionally, was male-only. As the National Student reported, “Mr Cox gave in, and ‘bought their votes with penny buns’. That was the way some brutes of men put it.”108

But Cox had more going for him than such tactical shrewdness. He was the best speaker in the Society that year, winning the Gold Medal, and his opponent clearly recognised that this was an electoral advantage. Cahir Davitt, also a former O’Connell School boy, recalled being canvassed by Costello, and replying evasively that he hadn’t been to enough meetings to judge which of the candidates was the better speaker. Costello replied “that of course if that were the only matter that was to be considered I should vote for Cox”.109 As it happened, Davitt voted for Costello, presumably because the school tie trumped eloquence; but the exchange is indicative of the future Taoiseach’s diffidence, modesty, and lack of a killer instinct—it is difficult to imagine Cox giving a similar reply.

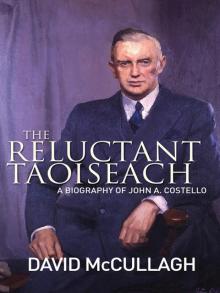

The Reluctant Taoiseach

The Reluctant Taoiseach